The most pressing issue in healthcare centers today isn't the emigration of Medical Officers (MOs), but the severe shortage of specialist doctors.

While the two national hospitals and 20 teaching hospitals haven't yet experienced the impact, this crisis is severely affecting provincial hospitals, district hospitals, and primary healthcare centers.

Currently, there are 2,851 approved specialist doctor positions in Sri Lanka, but the Ministry of Health reports that only 2,574 of these positions are currently filled.

Indeed, the situation is complex. Currently, there are 2,039 patients in hospitals, and the retirement age is set for December 31, 2024. If the retirement age is maintained at 63, only around 70-75 of the existing doctors will retire, which doesn't significantly worsen the shortage.

However, if the retirement age is lowered to 60, a more significant problem emerges, with 310 doctors (15% of the current workforce) retiring on that day. The real issue lies in the fact that the cycle of retiring specialists being replaced by new ones is disrupted. This disruption is driven by factors like doctors going abroad, leaving the service, or joining medical colleges and private sector hospitals.

The shortage of anesthesiologists is particularly concerning, with only 120 out of the approved 180 positions currently filled as of September 2023. The deficit stands at 60, and out of the 20 who completed their training abroad in the last two years, 9 have left the country for overseas jobs or haven't returned to hospitals for various reasons. Two have chosen to join universities within the country, further limiting the available pool of specialists to address this critical shortage

Given the circumstances, out of the existing shortfall of 60 anesthesiologists, it appears that only 9 positions can be practically filled. Consequently, the year is expected to conclude with a persistent shortage of 51 anesthesiologists.

In an attempt to address this deficit, the Ministry has compiled a list of 25 potential replacement doctors. However, this list faces its own challenges, as 6 individuals from that list have already left the country for overseas opportunities. Additionally, two others listed have not yet returned to Sri Lanka, while another two have not completed their training, further complicating the efforts to address this critical shortage.

Based on the situation, it seems that approximately 11 or slightly more positions can practically be filled from the replacement list. However, this still leaves an unfillable deficit of around 40 positions, which means that B-grade primary hospitals are unable to secure doctors to cover existing work or increase their capacity.

The shortage of specialist doctors is particularly severe in hospitals located in the interior of the country and the North East. For example, Ampara Hospital requires 20 specialist medical units, but 15 of these sections are already vacant. Only 5 categories have been applied for in 2024, further limiting the options for addressing this shortage.

This scarcity of specialists forces patients to travel to other hospitals such as Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Hambantota, or Monaragala, putting additional strain on those healthcare facilities. In Trincomalee General Hospital, there's a limited number of specialist doctors who have to cover patients at Kantale, Kinnia, and Muthur Primary Hospitals. The situation is equally dire in places like Kalmune, Nedavur, Pothuvil, and Samanthure, where patients are referred to Kalmune Hospital, leading to unbearable pressure.

In addition to the shortage of anesthesiologists, there's also a deficit in Gynecologists and Obstetricians. Out of 168 established positions, only 130 are currently filled, with 7 doctors having recently quit or retired and 8 leaving the country. This leaves the number of employees at 115, further exacerbating the challenges in providing essential healthcare services.

The situation regarding Gynecologists and Obstetricians remains challenging. Out of the 17 names on the 2023 supplemental list, two individuals are not reporting for duty, and three others are prepared to leave government service within the next two months. Fortunately, 12 new doctors will be employed. However, there is still a significant shortage of 18 gynecologists and obstetricians.

If the retirement age is lowered to 60, an additional 21 doctors will retire at the end of 2024. If it remains at 63, there are 8 doctors who will retire, including senior specialists from Castle and De Soysa hospitals, as well as 2 out of 3 specialists in Kalutara, resulting in a total of 18 vacancies.

In the field of Cardiothoracic surgery, 16 cardiac surgeons serve Sri Lanka's 22 million population across 5 units in the National Hospital, Kandy, Karapitiya, Children's Hospital, and Jaffna. If the retirement age of 60 is implemented, 6 of these surgeons (comprising all 5 from the Colombo National Hospital and one of the 4 in Kandy) will be required to retire, further intensifying the specialist shortage.

The situation regarding specialist heart surgeons is becoming increasingly critical. One doctor has already left the country, and another is set to go abroad soon. This leaves only 10 specialists remaining. What's even more concerning is that there's no specialist heart surgeon who has completed their training and is scheduled to return to Sri Lanka in 2024.

Furthermore, one individual who is currently on leave for foreign training has come to Sri Lanka and subsequently left again. There is a high possibility that the remaining three specialists in this field may not return, which would further worsen the shortage of these crucial medical professionals in the country. This highlights the urgent need for measures to address the retention and recruitment of specialist heart surgeons.

The situation is indeed dire, and the inevitable consequence of this shortage is the potential closure of several cardiac surgery units. This not only affects the availability of specialized care but also poses a significant risk to patients. Approximately 10% of patients on the surgery list for longer than two years face the tragic outcome of losing their lives. Moreover, the completed Anuradhapura unit and the proposed Kurunegala and Batticaloa units lack the necessary experts to begin operations, adding to the challenges in providing essential medical services in these areas.In addition to the shortage of cardiac surgeons, there's also a significant deficit in the field of Histopathology. Out of 75 approved positions, only 48 are currently filled, leaving approximately 23 to 25 vacancies. Furthermore, 10 doctors who diagnose patients in this critical field are already working abroad, further exacerbating the shortage of these specialized medical professionals. Addressing this shortage is crucial for maintaining the quality of healthcare services in the country.

The challenges in specialist medical services are becoming increasingly evident. Two doctors have recently retired, and if the retirement age is lowered to 60, another 10 will exit public service by December 31, 2024. These specialists play a crucial role, with the three doctors at the National Hospital conducting 40,000 tests related to various diseases in 2022. The scarcity of these specialists, who diagnose diseases including cancer, threatens the affordability of healthcare in the country.

The situation is also straining other healthcare professionals, such as acting officers in the Northern Province and in Ampara. Laboratory technicians, who are already understaffed, are bearing additional burdens, further impacting the overall healthcare system.

This shortage isn't limited to specific fields; it extends to various departments of specialist medical services, including ophthalmology, pediatric cardiology, neurosurgery, emergency medicine, intensive care units, surgeons, otolaryngologists, and psychiatrists. These examples, along with nearly 20 others, underscore that the real medical shortage lies in specialist medical services, rather than the general medical services promoted by trade unions.

The Ministry of Health faces the challenge of addressing this shortage, and the government's current approach is to maintain the proposed retirement age for specialists between 60 and 63. This aims to reduce the number of retiring specialists from 300 to 60, although it comes with demands from doctors, nurses, and laboratory technicians to extend their own retirement ages.

The ongoing conflicts within health centers involving gangs, groups, and castes have persisted for four decades, adding another layer of complexity to the already challenging healthcare landscape in the country. Addressing these multifaceted issues will require comprehensive and sustained efforts from both the government and healthcare professionals.

Attracting new doctors to train with specialists in peripheral services is imperative and requires the immediate implementation of a protective package. This package should include economic incentives and privileges to entice experts to work in rural and challenging areas, prioritizing locations outside of Colombo and its suburbs.

The crisis is affecting approximately 43 out of 61 specialist medical groups, and with the exception of medical administration, forensics, community health, food and nutrition, all sectors are gradually sinking into this crisis. A significant concern arising from the mass retirement of specialists is the absence of experienced professionals to train the next generation of medical practitioners. The consequences of this gap will manifest in years to come.

Extending the retirement age of medical specialists is essential to mitigate this crisis. However, there are challenges in bringing retired experts back to work, as they have faced delays in receiving their salaries due to the Public Service Commission's approval process.

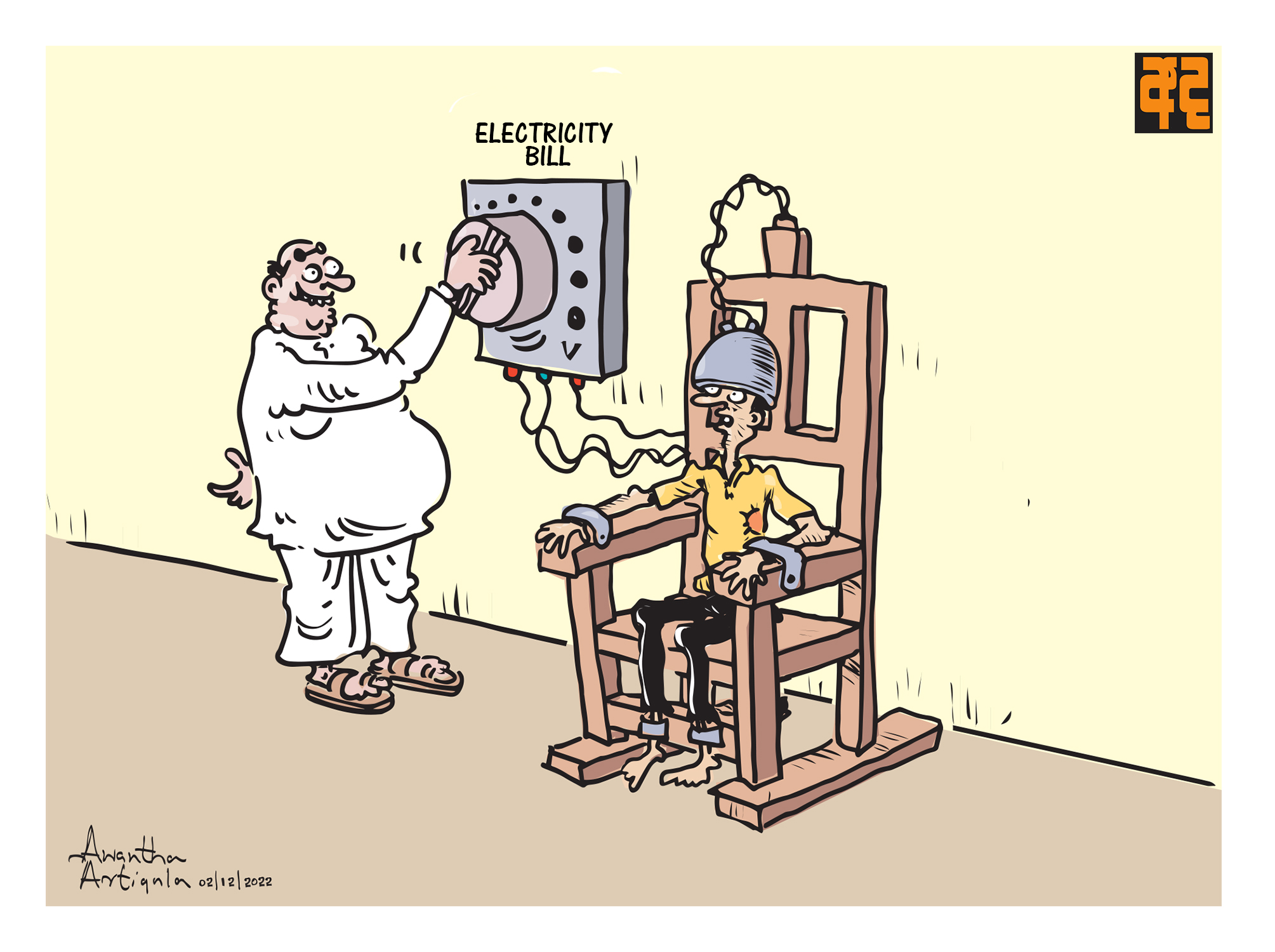

The healthcare crisis extends beyond the medical field, affecting every sector of the public service in the country. In response, Circular Document 14/2022 has proposed to restrict government employees, including doctors, from going abroad. It's important to note that such restrictions may be seen as uncivilized, and the country should not resort to coercive measures similar to those in Cuba or North Korea to prevent citizens from seeking opportunities abroad.

The Ministry of Health needs to take more proactive measures to control the exodus of doctors for various reasons, both local and foreign. Updating doctors' service contracts, improving human resource management, implementing formal data systems, and addressing equipment shortages are all critical steps to stabilize the healthcare system and ensure the availability of skilled medical professionals for the population's health needs.

The delays in shipping repairs and acquiring necessary accessories are indeed a concerning aspect of the healthcare system's challenges. In some sectors with high demand, the current procedures of the Ministry of Health allow doctors to leave their service after paying back just a month or two of their salary earned abroad. Weak policies and management strategies create an environment where specialists can easily opt to leave the country and join private practice, exacerbating the brain drain issue.

Circular Document 14/2022 highlights the difference in how doctors taking foreign leave are labeled as 'loss of doctors to the country' while other government employees are granted leave and labeled 'Rata Viruwan'. This discrepancy underscores the need for a comprehensive and fair approach to managing the retention of medical professionals.

The brain drain of physicians has been a historical challenge, but today it is compounded by management issues and administrative failures. The delay in preparing the 2023 list of specialists for 10 months and the uncertainty surrounding the release of the proposed 2024 list further exacerbate the healthcare system's collapse, ultimately affecting patients and their families.

It is regrettable that doctors' unions, despite understanding the gravity of the health crisis, sometimes turn it into a platform for their professional gains. Addressing these complex issues requires a collaborative effort between healthcare professionals, administrators, and policymakers to ensure the well-being of citizens and the sustainability of the healthcare system.

Ranjith Keerthi Tennakoon

(President's Director General for Community Affairs)

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.