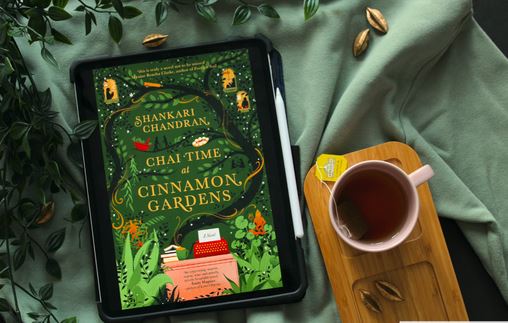

Shankari Chandran’s Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens, an intergenerational epic confronting Australia’s uneasy relationship with multiculturalism and postcolonial trauma, has won the 2023 Miles Franklin literary award.

Chandran, a Sydney-based lawyer of Tamil heritage, collected the prestigious $60,000 award in Sydney on Tuesday night.

The judges praised Chandran’s third novel, set in an aged care facility in contemporary western Sydney and Sri Lanka’s brutal civil war, as an accomplished work of character, dialogue and action.

“It treads carefully on contested historical claims, reminding us that horrors forgotten are horrors bound to be repeated, and that the reclamation and retelling of history cannot be undertaken without listening to the story-tellers amongst us,” the judges’ said in a joint statement.

But Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens very nearly didn’t get written, let alone published, Chandran said.

Sales for her second book, a futuristic thriller titled The Barrier, were modest and publishers had outright rejected her follow-up manuscript.

“In my heart I felt [Chai Time] would never be published in Australia, which gave me the freedom to write in the way that I wanted to write, with complete honesty,” she said. “And not only was it a liberating experience, it also just felt like the right time for me to finally explore the issues of race and identity in Australia.”

Chandran’s parents, both doctors, fled Sri Lanka as the country stood on the precipice of civil war, first to the UK where the author was born, then to Australia three years later.

Chandran grew up in suburban Canberra, in constant dialogue with herself about where she fitted in and the terms under which acceptance was granted.

“The complexity and diversity of who I am and my family history, my cultural history, my religious and spiritual practices, even just the colour of my skin, isn’t necessarily always accepted here,” she said.

“I’d never felt comfortable enough, courageous enough, to explore this openly through literature. It was an issue that I might talk about with myself, it’s an issue that I might talk about in the very safe space with other Sri Lankan Tamils. And you would talk about it quietly, almost sort of looking over your shoulder because you’re not supposed to articulate these things. Not just because it doesn’t feel safe to articulate them but because it doesn’t feel right. It feels ungrateful.”

Gratitude is a recurring theme in the book. As one character observes, new, non-Anglo Australians, be they refugees or immigrants, have the sense they are “always on probation”. There is an expectation, if not demand, from white Australia of unwavering gratitude towards a nation that has provided sanctuary from whatever “shithole countries”, as one shock jock in the book puts it, they fled.

“It is that expectation of gratitude that rendered me silent, certainly throughout my childhood and into adulthood,” Chandran said.

The soothing title of the book and verdant cover are intentionally deceptive. What starts as a narrative about the gentle folk of a rest home, tended by model carers, descends into violence, intergenerational trauma, grief and rage as the past and outside world seep in.

An act of postcolonial activism – the removal of a statue of Captain Cook in the grounds of Cinnamon Gardens – sets off a chain of events, ripping apart a community’s seams, stoking a social media frenzy and provoking racial violence.

“There certainly is a lot of rage in the book,” Chandran said. “But I feel like a lot of my work begins from that place of rage. But through the writing, through the thinking and in the reflecting, it goes to a place of love. I hope.”

In between working full time as head of sustainability for an ASX 200 corporation and parenting four teenagers, Chandran began work on Chai Time as the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements faced backlashes from quarters nursing grievances about white male disempowerment. She continued writing through Covid-19, when anti-Asian sentiment crept into many communities and caused her to re-interrogate her family’s place in the world. What are we willing to normalise? What are we willing to accept?

“In many ways the novel is less about suggesting reasons for our difficulties with race, but just asking: why is it so hard? It’s not just that there’s a problem with race, but there is a problem in the way that we talk about it and allow ourselves to talk about it – and more importantly, don’t allow ourselves to talk about it,” she said.

The 2023 judges were the State Library of NSW Mitchell librarian and chair Richard Neville, author and literary critic Bernadette Brennan, academic and translator Mridula Nath Chakraborty, critic James Ley and academic and poet Elfie Shiosaki.

(theguardian.com)