Whenever I am confronted with the challenge of writing about subjects and disciplines, the frontiers of which I am not quite certain, I have an “infantile tendency” of referring to well-known dictionaries and lexicons.

Interestingly, this failing in me has always pushed me on to the correct path, ever enabling me to grasp the cardinal principles of the disciplines concerned.

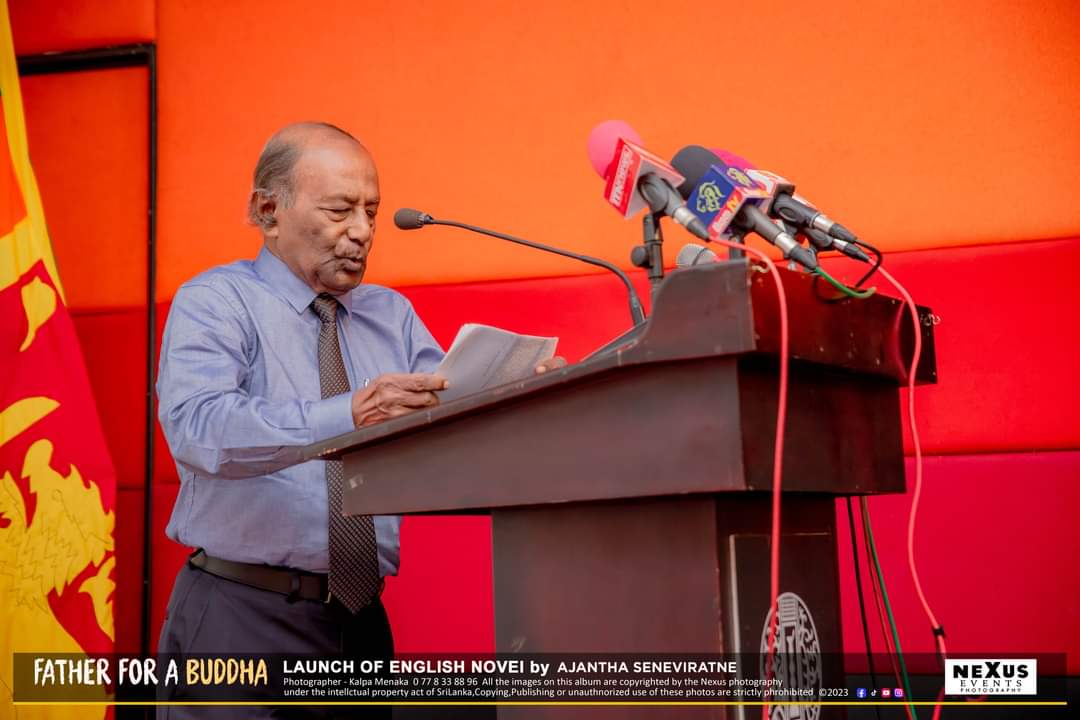

And now, there is a challenge posed on me, to write a foreword to Ajantha Seneviratne ’s first novel in English - Father for a Buddha.

To begin with, it is a work of literature - a creative endeavor - although the main character involved therein is a historical personality, who fathered Prince Siddhartha, destined to become the Enlightened Buddha, the supreme human being of all times.

However, King Suddhodana, although a formidable character among Buddhist laity, very scant attention is paid to him in the Buddhist canonical literature, overshadowed by greatness of the Buddha.

As I perused Ajantha’s manuscript, it dawned on me that his sole attempt was not to reconstruct the life of the Buddha, but to portray the character of the great monarch Suddhodana, in a literary as well as historical perspective.

Nevertheless, this novel is essentially a work of literature.

What then, is literature?

I refer up the lexicons of repute. I was highly disappointed when I referred up the Oxford Dictionary which defined literature merely as “written works, especially those regarded as having artistic merit.” To come to such a very general superficial definition of a vast subject as literature, why on earth should one refer to a dictionary? And Oxford, for that matter!

According to my little knowledge of the history of classical literature, the first reference I have encountered is the 19th and the 20th stanzas of the Yamaka Vagga (The Pairs) of the Dhammapada, wherein the term “sahitan bhasamano” occur twice.

Scholars agree that the word “Sahita” in this context, is a clear reference to the Tripitaka - the Buddhist canonical literature.

One cannot challenge the vastness of that reference to the entirety of the Dhamma, where Juan Mascaro in his brilliant rendering into English of The Dhammapadha (The Path of Perfection) refers to, as “holy words". To him, “Sahita” or literature are “holy words”.

“Holy words.” What else could good literature be? And why not we elaborate further, as to what these holy words are, or what they should be?

In my “infantile exercise”, I lastly refer to Webster. And this is what Webster has to say, what literature is about.

“Written works which deal with themes of permanent and universal interest, characterized by creativeness and grace of expression….”

This, I earnestly believe, is the proper definition in which Ajantha Seneviratne’s wonderful novel could meticulously be accommodated.

As the definition goes, this is a work of literature, which deals with a “theme of permanent and universal interest”, since the story is webbed around the monarch Suddhodana, one of the greatest personalities in the history of mankind.

Apparently, the author portrays the character of the protagonist, utilizing faculties of meaningful imagination. And “grace of expression” is manifest in many instances, as the story gradually reaches its climax.

When carefully going through Ajantha’s manuscript, I was overwhelmed by the wealth of material he has conscientiously collected about the life of King Suddhodana and how beautifully he has reconstructed them into a narrative of rare distinction.

As an adept narrator, he collects, selects, sifts and arranges in proper order the material he has before him, pertaining to King Suddhodana’s character and re-creates it into a highly readable narrative of artistic acumen blended with creativity and skills of fine craftsmanship. And the ultimate outcome is a historical personality immortalized in literature.

How beautifully the author has transformed the character of Suddhodana from a mundane position culminating step by step into a higher level of spiritual attainment is fascinating indeed.

In this beautiful narrative, as I reached the end of my journey, I must frankly admit that I was on the brink of tears. It was soothingly emotional and was a real burden to my heart.

Any sensitive reader who reaches the conclusion of the narrative, I am certain, would find his or her eyes welled with tears. Those are not tears of pain or remorse, but of joy, at the realization of human greatness, compassion and above all, selflessness.

Out of all religious literatures – if you do not contest my assertion as a misnomer – I am encouraged to say that Buddhist literature is the vastest unfathomable repository of human behaviour which is ever widening towards infinite horizons, even the present day.

There is still ample material in the life of the Buddha, his disciples and many significant historical personalities that figured during Buddha’s time and came into the folds of the Buddhist Order.

Ajantha’s novel, I believe, should be an eye-opener to narrators engaged in the reconstruction of great personalities of Buddha’s time buried under the sands of time.

I came into contact with Ajantha Seneviratne under somewhat extra ordinary circumstances during my second tenure as the Chairman of the National Library and Documentation Services Board, during which time we were engaged in a new project with the collaboration of Sri Lanka Telecom, namely "Kiyawamu.lk."

Although we could not bring the project into the desired completion owing to political audacity, ministerial lethargy and bureaucratic bottle-necks, of course from our side, I was left with a host of personal friends who were higher officials of the Telecom at the time.

And out of them, Ajantha was a notable exception. Apart from being a very able and adept administrator and manager at Telecom and later as the CEO in charge of Sri Lanka Telecom PEO TV, who was also the concept creator of Charana TV, I was able to discover his creative literary talents as well. Since then, I have been carefully following his rise as a writer.

He was, even at that time, engaged in many literary pursuits, especially in the field of fiction. The main trait I found in him as a promising writer was his readiness to learn and the ability to adjust himself to compelling situations.

I profusely congratulate Ajantha in his bold attempt to immortalize King Suddhodana in the field of Buddhist literature and look forward to many of his literary achievements in the near future, both in Sinhala and English.

Dr. W.A. Abeysinghe