How to End Sri Lanka’s Food Crisis

Amita Arudpragasam

Last month, as the rupee depreciated and inflation rose, panicked Sri Lankans queued up for hours to purchase scarce supplies of sugar, rice, lentils, and milk powder. Sri Lanka depends on imports for essential goods, but it struggles to pay for them, especially given its history of weak export performance. Over the last few years, the problem has morphed into a full-blown sovereign debt crisis.

The country is expected to pay back $29 billion in debts over the next five years, and interest payments alone currently make up more than two-thirds of government revenue. Since March 2020, the government has imposed severe import restrictions to address the problem, setting off a dangerous chain reaction in the process.

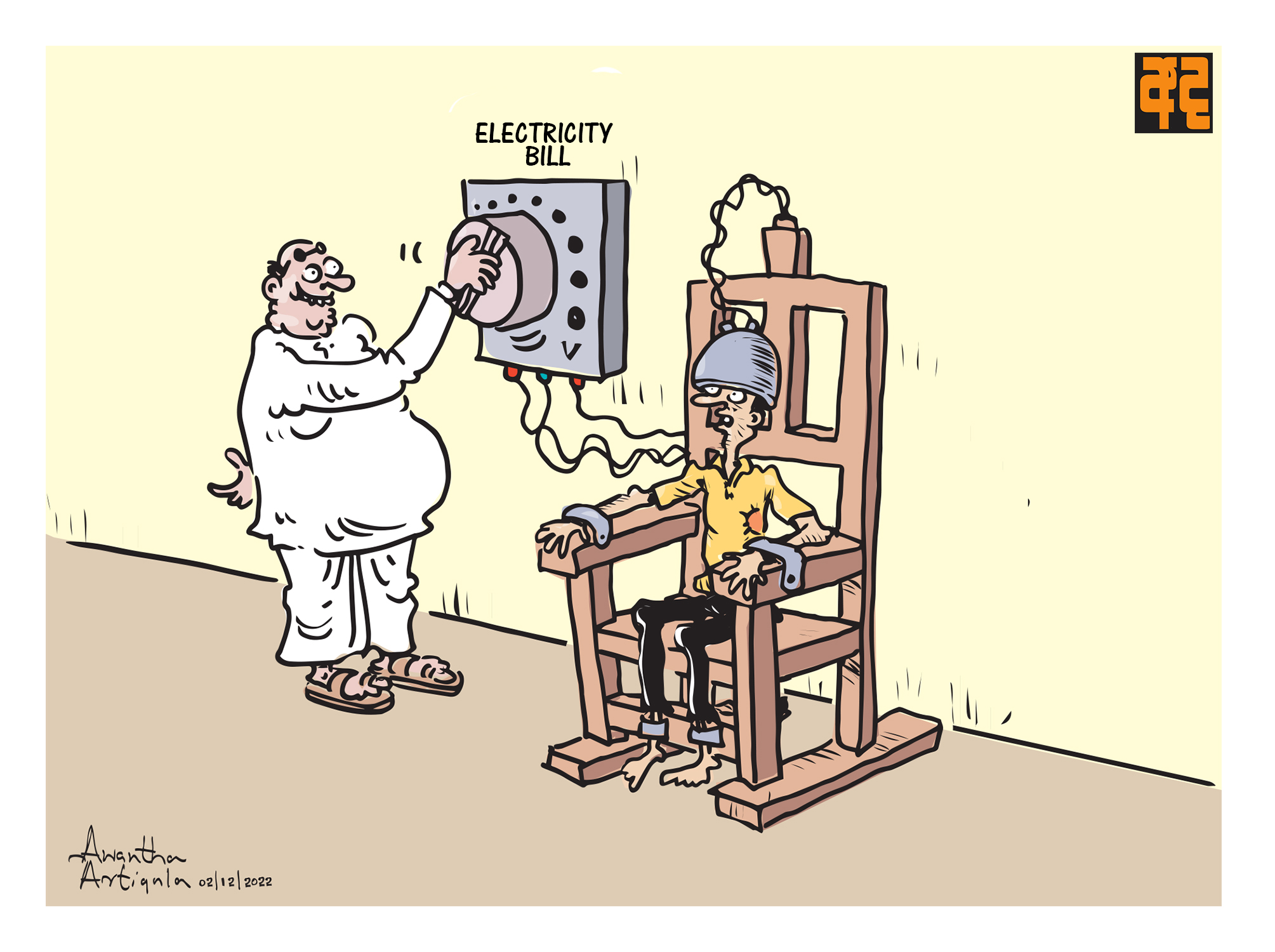

First, the prices of basic commodities soared. As the public grew restless earlier this year, Sri Lanka’s trade minister said the government would impose price controls and rationing for 27 essential food items. But the traders, who purchased these goods at higher rates, refused to release them into the market for less than what they’d paid. It was not long before there were shortages of several staples. On Aug. 30, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa invoked the country’s public security ordinance to stop the hoarding. That act can only be exercised “in view of the existence or imminence of a state of public emergency.” The country was thus in a state of emergency.

The new status is deeply concerning, as civil society groups have pointed out, since Sri Lanka has a long history of human rights abuses under emergency rule. Emergency regulations—which prevail over all law except the constitution—have previously been used to shut down newspapers, imprison political opponents without trial or charge, and destroy evidence of possible extrajudicial executions. As the main opposition party said, the designation may move the country “further in the direction of authoritarianism.”

Despite declaring a state of emergency in response to food-related shortages, the same government denied there is even a food crisis. The government line is shortages, if they exist at all, are only temporary. “People won’t go hungry,” insisted Sri Lanka’s state minister of finance in an interview with Al Jazeera. But even if current food shortages are indeed temporary—a result of short-term price controls and hoarding—next year they could well be widespread and enduring due to controversial new policies.

On April 29, Rajapaksa announced that Sri Lanka would replace all chemical fertilizers with organic substitutes, a mammoth transition that has not worked in any other country. Rejecting advice to transition the country in a phased manner, the president banned a series of agrochemicals just days later. The policy—aimed perhaps at preserving foreign exchange and justified as a method to reduce noncommunicable diseases—is expected to have disastrous consequences.

Without fertilizer, paddy yields will plummet and Sri Lanka’s tea industry—the country’s second largest export earner—will be devastated. Without agrochemicals, leaf disease also threatens to lower yields in the rubber industry—another major export earner. Not only will the policy make it harder to afford necessary imports, but as domestic yields drop, it will also increase the likelihood of a more sustained food crisis.

Workers load sugar into a container truck at a private warehouse after Sri Lankan officials seized the stocks as part of a crackdown on hoarding in Wattala, Sri Lanka, on Sept. 1.Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP via Getty Images

Sri Lankan officials and policymakers continue to blame the COVID-19 pandemic for the country’s faltering economy. Lockdowns and border closures have depressed global economic activity while foreign direct investment and capital have vacated emerging markets. For debt-ridden developing countries, the pandemic’s economic fallout will be far worse than the 2008 financial crisis.

Challenging external conditions, however, do not exonerate Sri Lanka’s policymakers. Credit agencies like Moody’s Investors Service and S&P 500 have consistently downgraded the country, demonstrating low confidence in its ability to pay back its debts. That’s mainly because Sri Lanka’s economic shortcomings are structural: a low tax-to-GDP ratio, prohibitive barriers to trade, a bloated public sector, and high costs of doing business. These deficiencies have existed for more than a decade, long before the pandemic.

Instead of addressing structural shortcomings, the government is making them worse. In 2019, it lowered taxes for the wealthy and increased tax holidays for corporations. In 2020, it made trade even more restrictive by imposing blanket import bans, which have created instability, shortages, and black markets. Import restrictions are at their highest since the 1970s, when the country was nearly a closed economy. Analysts are now drawing comparisons to that decade, which is the last time Sri Lanka saw shortages of essentials like rice, bread, and sugar.

Fifty years ago, Sri Lankan policymakers were also concerned about excessive international dependence—but understandably so. They were responding to the oil crisis, World War II, and a fall in rubber prices post-Korean War. Then-Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, whose mantra was “produce or perish,” promoted self-sufficiency as a development strategy.

Along with her coalition partners on the left, Bandaranaike imposed import restrictions and severe austerity measures, including conditions on what people could eat. As unemployment and inflation soared, she introduced price controls to mitigate hunger and drew on emergency powers to repress protests. The rationing and queues that followed are an enduring part of Bandaranaike’s legacy, and the fallout from those policies would inspire a decade of extensive economic liberalization.

After remarkable electoral success in November 2019, Rajapaksa embarked on a project similar to Bandaranaike’s. His administration would promote “self-sufficiency” through the development of 2 million new home gardens—a strategy also used in the 1970s—and would ban imports of at least 16 different crops.

But Rajapaksa is doing the opposite of what development economists generally recommend. According to experts, countries should move away from low-productivity sectors, such as agriculture, into high-productivity sectors, such as information and communications technology. Even though 30 percent of Sri Lanka’s labor force is employed in agriculture, the sector only contributes to about 8 percent of its GDP.

Nonetheless, the government continues to subsidize and expand agriculture. As farmers struggle to educate and transition their relatives into higher wage jobs, Sri Lanka’s urban and middle classes romanticize the physical labor of the farmer, privileging the idea of “gama-pansala weva-dagaba” (“village temple, irrigation tank shrine”) or the village as the spiritual and productive heart of the nation.

Rajapaksa’s isolationism, unlike Bandaranaike’s in the 1970s, is shaped less by global economic events than by an aversion to the West and a cultivation of conservative support, which views international powers as a threat to Sri Lankan sovereignty. After Sri Lanka’s civil war ended in 2009, the government faced increased human rights scrutiny and international pressure. According to a United Nations investigation, for instance, Sri Lankan security forces may have committed war crimes or crimes against humanity aimed predominantly at the country’s Tamil minority. In response, xenophobic rhetoric only intensified, including in Rajapaksa’s 2019 presidential campaign.

People stand in a queue to buy kerosene oil used in cooking stoves as Sri Lanka faces shortages of imported cooking gas and sugar in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on Aug. 19.Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP via Getty Images

The regime could stop the human rights abuses that have made foes of the country’s longtime allies to focus instead on the economic reforms Sri Lanka so desperately needs. But instead, it continues to sow discord and traumatize minority communities.

For example, the government forcibly cremated Muslims and Christians who died of COVID-19, claiming without evidence that burials contributed to the virus’s spread. It continues to intimidate journalists and protesters. As government representatives reiterated barren commitments on human rights and reconciliation at the U.N. Human Rights Council this month, Sri Lanka’s minister of prison management broke into a prison and drunkenly forced Tamil inmates to kneel at gunpoint.

Continued human rights violations will come at a high cost for the Rajapaksa regime. In particular, Sri Lanka stands to lose its preferential trading status with the European Union. In June, the European Parliament passed a resolution addressing the dire human rights situation in Sri Lanka. It called on the government to review and repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act—a draconian law that has been used to target, torture, and sexually abuse minorities. An EU delegation is in Colombo this week to review Sri Lanka’s commitments under the trading arrangement, but it is unclear whether the Rajapaksa administration will make any progress toward amending the law.

A temporary suspension of Sri Lanka’s preferential trading status would be a huge blow to its economy since the EU is Sri Lanka’s second largest export market, absorbing 22.4 percent of its exports. Even without this suspension though, prices continue to rise.

Many Sri Lankans have had enough. In June, the public was infuriated when government-owned Ceylon Petroleum Corporation announced a fuel price hike. Unable to protest due to the lockdown and selectively applied quarantine laws, citizens took to social media to register their frustration. Just two years ago, the Rajapaksa family’s party slammed its predecessor’s policy for increasing retail fuel prices.

Urging motorists to use fuel sparingly, Sri Lanka’s energy minister tweeted, “the reality is that we are in a foreign currency crisis,” on Aug. 17. It’s as if the government was finally forced to acknowledge an economic crisis that has plagued the country for years. On Sept. 7, Sri Lanka’s “severe foreign exchange crisis” was also acknowledged by Basil Rajapaksa, the newly appointed finance minister and younger brother of Gotabaya. “We admit that there has been unnecessary spending, waste, and corruption in the past, not only limited to a certain period but for a long period,” he confessed in his surprisingly frank maiden parliamentary speech.

It’s impossible to deny there’s a problem. Every newspaper brings a new story of calamity—whether that’s the biggest maritime disaster in Sri Lanka’s history, a multimillion-dollar sugar scam, the destruction of Sri Lanka's rainforests destruction of Sri Lanka’s rainforests, a fatal new wave of COVID-19, possible fuel shortages fuel shortages, or Sri Lanka’s new state of emergency.

The combination of external crises and poor policy management may make Sri Lanka one of the first emerging markets to default post-pandemic. To recover from this crisis, Sri Lanka must do far more than acknowledge the scale of the problem.

Instead of forcing its citizens to starve, the government needs to enact structural reforms economists have been recommending for years. It must lift its suffocating import restrictions, raise taxes on those who can afford them, and encourage movement away from agriculture. And it must either abandon or slowly phase in its ambitious plan to switch to organic fertilizers.

Finally, the country must end human rights abuses, release political prisoners, and repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act—this time not only in the name of basic human decency but also to save its economy. To achieve that, either policymakers need a radically different approach or Sri Lanka needs radically different policymakers.

Amita Arudpragasam is a Sri Lankan writer and a graduate of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and Princeton University.

Amita Arudpragasam is a Sri Lankan writer and a graduate of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government and Princeton University.

Twitter: @aarudpra

(Source : foreignpolicy.com)