“P2P” was hardly reported in Colombo based mainstream media, though there was later reference to the “civil disobedience” campaign in North and East led by the Federal Party (FP) in 1961. PM Mahinda Rajapaksa’s statement subsequently defined as “personal observation” was subordinated to an “expert committee” projected as the “supreme” body that decides anything and everything on COVID-19 pandemic.

The “P2P” protest compared with the “civil disobedience” campaign in 1961 is spoken with new hope that it could once again lead to democratic, non-violent Tamil nationalist politics. Comparison is on mass participation across Northern and Eastern Province. Meanwhile Colombo’s civil society analysts wish to see PM Rajapaksa’s statement on burials as one that reflects pressure from the Muslim world, and as an effort to capitalize on the official visit of Pakistani PM Imran Khan ahead of the UNHRC resolution.

There is political misreading of the two issues though. Especially in the reading of PM Rajapaksa’s statement on “burials”. Two important political factors remain ignored in both cases. First is the fact, ethno-religiously fractured and divided Eastern Province in particular and Tamil Muslim communities in general that nurtured hatred more than amity against each other for decades, was suddenly seen marching through streets together against the Sinhala-Buddhist dominated Colombo government. A major political factor ignored in most explanations and analyses.

That “unity” in the context of “this government denying burials for COVID-19 related deaths” needs to be factored in, when understanding the “P2P” phenomenon. In the East, there were friction between Tamil and Muslim communities though not in loud tones, perhaps before 1948 Independence as well. Post-independence, tussle for agri-land between Tamil and Muslim farmer populations in the East increased with Sinhala colonisation from D.S. Senanayake’s time.

With Tamil nationalism taking up arms, friction between the two communities came to open play. LTTE dominated areas in the East saw Muslim owned land being grabbed and distributed among Tamil people. This led to more hatred and conflicts between the two communities, the State security forces capitalised on.

This politico-military situation basically cemented a permanent rift between Tamil and Muslim communities that reached outside the Eastern Province too. The LTTE high command taking a politically stupid decision in treating all Muslim people as “traitors” and expelling traditional Muslim residents from Jaffna and Vanni, sealed the issue in favour of Sinhala-Buddhist politics. Within a wholly corrupt political system, Muslim political leaderships could find more than enough excuses to play politics with Sinhala-Buddhist dominated governments, keeping the Muslim vote as anti-Tamil.

With LTTE completely eliminated, post-war situation that turned extremist Sinhala-Buddhist violence against the Muslim community still kept them away from Tamil politics, though their vote went en-bloc against Rajapaksas in 04 consecutive elections; 2015 January and August elections and again in 2019 November and 2020 August elections. In both 2015 and 2020 parliamentary elections they had their own Muslim candidates to vote for, even outside East.

This Tamil Muslim divide that wrapped everything from politics to culture including trade and commerce, suddenly disappeared on 03 February when the “P2P” protest left Muslim dominated Pottuvil, a town in the Southern corner of Eastern Province. Muslim political party leaders were absent, but not Muslim communities in the East. The “P2P” that rejected national independence on 04 February was initiated by a collective of Tamil social organisations that sought political backing of TNA Batticaloa MP Shanakiya Rasamanickam. He organised the formal endorsement of “P2P” by the TNA leadership with Jaffna district MP Sumanthiran personally participating. Though with no Muslim leaders around, the “P2P” protest gained political strength from Muslim community participation that helped swell the numbers too.

This ethno-religious “unity” was right on the ground. It was a democratic alliance of neighbouring communities in a majority rural society. It was not based on political parties signing MoUs in Colombo. It was not one for “press statements”, “voice cuts” and electoral gains. It was not merely anti-Rajapaksa as their vote was, at elections. This “unity” reflected an “understanding” between Tamil and Muslim people as equally oppressed communities by Sinhala-Buddhist extremist politics. They thus came together in total opposition to the Sinhala-Buddhist ideology that defines the present “nation State” and the Rajapaksas' led government. That is what PM Rajapaksa was politically very much concerned about and what others did not read and did not know to read.

PM Rajapaksa knew Tamil nationalism began challenging the Sinhala-Buddhist State ever since they adopted the resolution for a “separate Eelam State” in 1974 as TULF. He perhaps knows the TULF contested on that platform in 1977 galvanising almost 90 per cent Tamil support for it in North-East. He also knows the Muslim community was never on that page, though Tamil politicians kept talking of “Tamil speaking people in N-E”. Would “P2P” change that N-E political landscape altogether? That “Unity” the “P2P” demonstrated on the streets from 03rd to 07th February was what Mahinda Rajapaksa was very much concerned about.

The second political factor he was very much disturbed about is massive crowds coming on the streets. He knows by experience that massive protests do change governments, though not in a day or two. His decision on “COVID-19 related enforced cremations” thus came 02 days after he saw unprecedented large crowds choc-a-bloc on the streets in Jaffna on 07 February inching their way to Polikandy. That would have definitely reminded him of the “Pada Yathra” he led in 1992 that inched its way to Kataragama. I can still remember his “proud smiling face” when I told him people are struggling to join the “Pada Yathra” at Tissa, to his very inquisitive question, “Where about is the end?”

He was received at the Kataragama “Gam Udawa” entrance by Madam Vivienne Gunawardne with her LSSP Women’s Federation activists, defying her party decision that was to boycot the “Pada Yathra”. About 16 kms from Tissa, Mahinda was the hero flagged by a host of opposition political leaders, MPs, and trade unionists wanting to be captured on camera posing with Mahinda. All that taught him “People’s collective strength” has no substitutes.

That period was not very much different to the present political context. President Premadasa was feared in the Sinhala South as a very ruthless leader and one who could never be challenged. He had crushed all internal opposition led by the two most charismatic and intelligent leaders, Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake, JRJ groomed for the UNP. That was also when the SLFP leadership was in tatters. Family brawls for SLFP leadership were in the open and Madam B was unable to even hold SLFP Central Committee and parliamentary group meetings for months at a stretch.

Yet it was the “Pada Yathra” popularly called “Mahinda’s Pada Yathra” that led to many other organised protests and proved President Premadasa can be openly challenged on the streets. It gave confidence for People to publicly oppose President Premadasa even on local issues. It once again activated SLFP electoral leaders. That made it possible to electorally defeat Premadasa’s UNP at three key provinces Southern, Western and North-Western (Wayamba). Assassination of President Premadasa by the LTTE on first May three weeks before the elections, did not provide much sympathy for the UNP to win them.

There is also another mass protest that led to change of government in 2001. Mahinda was invited to join it, but he declined. In mid-2001 with the JVP joining President Chandrika K’s government to form a crazy government termed “Probationary”, the UNP rallied other opposition forces in a mass protest that laid siege on Colombo. It called for immediate adoption of the 17 Amendment and then dissolution of this “probationary” government. It was a successful mass protest that pushed President Kumaratunge to dissolve parliament. Elections held in December, the UNP led by Wickramasinghe who was ridiculed as a “never victorious” leader, won elections and formed a UNP government on 19 December 2001.

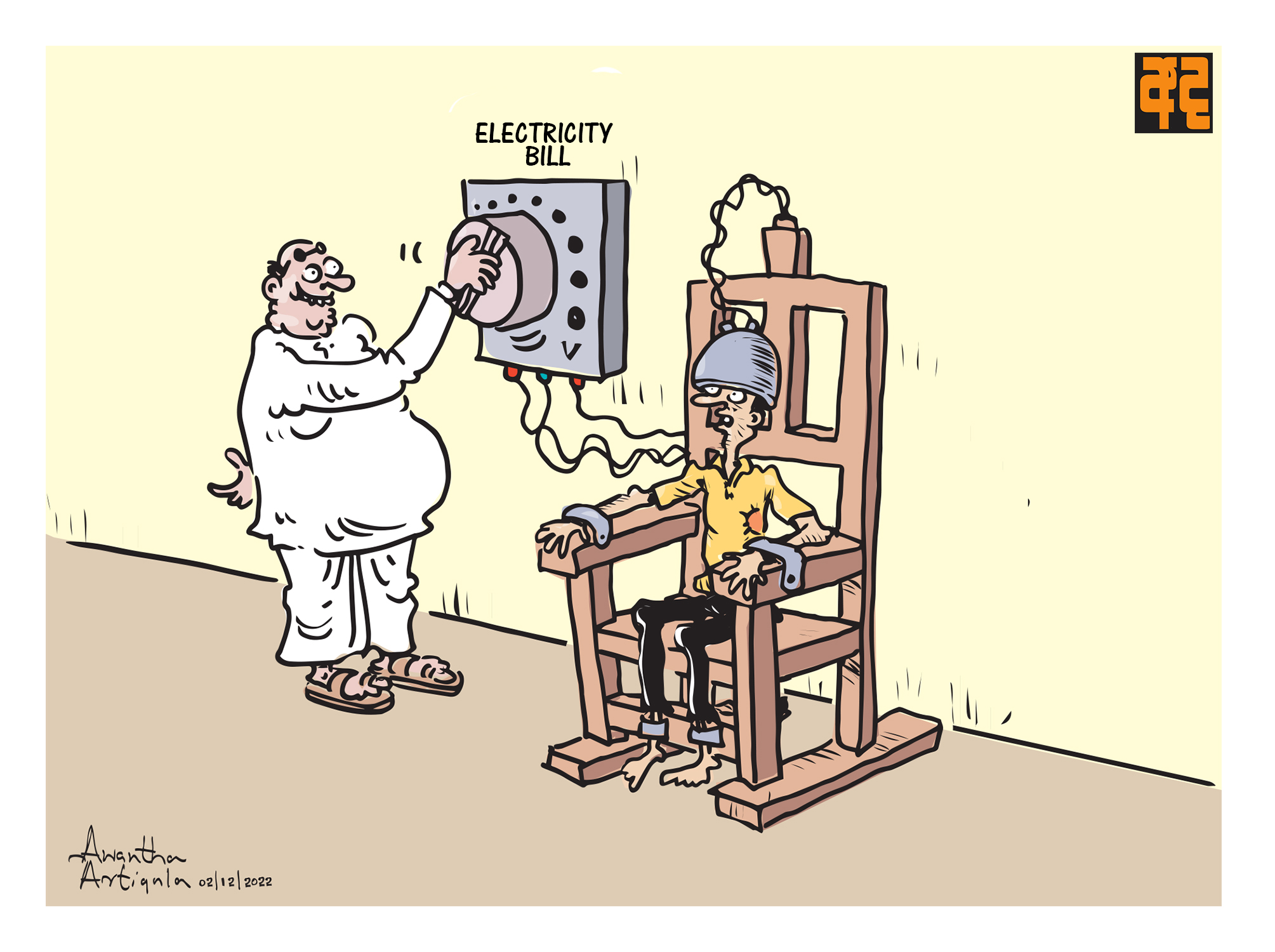

In short, Mahinda Rajapaksa is one who understands the “collective strength” of People on the streets. He understands better, what it could lead to if Tamil and Muslim People find “unity” among them as their uncompromising strength in challenging the government. He understands best, “unity” of the oppressed could go “viral” and Tamil and Muslim “unity” can embrace the Sinhala “poor” as well, when the government is seen as helpless in finding answers to increasing economic crises amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

His manipulation in changing the anti-Muslim projection of the government thus had nothing to do with Imran Khan’s visit and the UNHRC Resolution. It was all about facing this new and fast-growing Tamil-Muslim “unity” on the ground. He was totally mis-read by Sinhala-Buddhist political vendors who live by the day. And sadly, his government too cannot read its own fate politically as he reads it.

Kusal Perera

18 February, 2021

"P2P' and mis-read Rajapaksa on burials

The five day Pottuvil to Polikandy (P2P) protest march and Prime Minister Rajapaksa’s statement in parliament on COVID-19 related burials are two issues that are discussed separately, and judgements passed separately.